When the Going Gets Wurst...

Cassell Cave, WV

A survey trip with the Gangsta Mappers

September 21, 2002 (part 11)(part 1, part 2, part 3, part 4, part 5, part 6, part 7, part 8, part 9, part 10, part 11) | Photos |

- My Perspective on the Rescue

- Bob Robin's Report and photos (external link)

- Tom Kornack's Perspective

- First-hand Accident Details from Todd Leonhardt

- Tom's Digital Photos (external link)

The Cassell survey trips for me have settled into something of a routine. Nevertheless, I was excited to put together a team and continue work on my personal project area of the cave. I'd optimistically estimated that one good push could finish the Bratwurst and I was eager to get started. Gangsta turnout was sparse but I was joined by Tom Kornack, Bob Robins, and Edgard Bertout for the third foray into the lovely and remote Bratwust Passage of Cassell Cave. We were the only team was using the pit entrance today; the others were planning shorter trips to other parts of Cassell or to survey Willis-Cassell cave. The Bratwurst is profusely decorated and the two trips so far have been extremely rewarding. Sadly, all good things must be balanced out by some not-so-exhilarating experiences. We do this because it's fun... most of the time.

The Cassell survey trips for me have settled into something of a routine. Nevertheless, I was excited to put together a team and continue work on my personal project area of the cave. I'd optimistically estimated that one good push could finish the Bratwurst and I was eager to get started. Gangsta turnout was sparse but I was joined by Tom Kornack, Bob Robins, and Edgard Bertout for the third foray into the lovely and remote Bratwust Passage of Cassell Cave. We were the only team was using the pit entrance today; the others were planning shorter trips to other parts of Cassell or to survey Willis-Cassell cave. The Bratwurst is profusely decorated and the two trips so far have been extremely rewarding. Sadly, all good things must be balanced out by some not-so-exhilarating experiences. We do this because it's fun... most of the time.

Edgard and I modelling nice, clean Meander Helix caveralls. (Tom Kornack photo) |

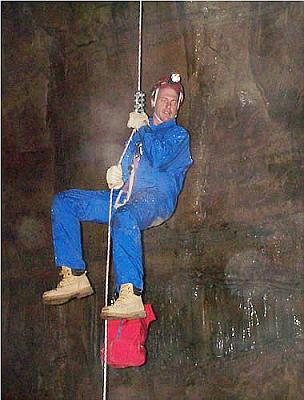

Edgard descends the pit. Still clean! (Bob Robins photo) |

The last two trips have been mostly concerned with pushing the main Bratwurst passage toward its unknown ends to the south leaving a couple major leads unchecked. While usually fairly informative in a qualitative way, the 1960's era map of this section bears zero resemblance to the reality we were exploring. Thus nobody really knew what we would find. I planned to finish off a couple of the leads on this trip and then continue the upstream survey through the same pretty, easy passage we'd navigated before.

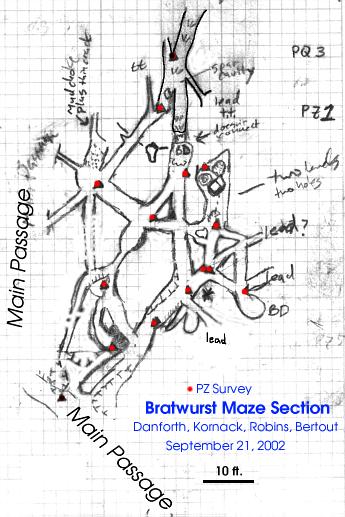

The last two trips have been mostly concerned with pushing the main Bratwurst passage toward its unknown ends to the south leaving a couple major leads unchecked. While usually fairly informative in a qualitative way, the 1960's era map of this section bears zero resemblance to the reality we were exploring. Thus nobody really knew what we would find. I planned to finish off a couple of the leads on this trip and then continue the upstream survey through the same pretty, easy passage we'd navigated before.  After a bit of lunch in the Lunch Room, the first place big enough to sit down and spread out, we started the PZ survey in a tight tube leading parallel to the main passage. Tom took point as usual trying out his new Indiglo-equipped survey instruments (ask him, it's very cool!) while Edgard took the other end of the tape. Bob recorded data and sketched profiles. The tight tube lead us into a startling maze of passages branching off in all directions, some of them connecting back with the main passage. On my slowly evolving sketch, I began to see that there was a roughly triangular grid-like layout. These passages were far muddier than the main corridor, probably because it hadn't been washed down to cobbles by the small stream.

After a bit of lunch in the Lunch Room, the first place big enough to sit down and spread out, we started the PZ survey in a tight tube leading parallel to the main passage. Tom took point as usual trying out his new Indiglo-equipped survey instruments (ask him, it's very cool!) while Edgard took the other end of the tape. Bob recorded data and sketched profiles. The tight tube lead us into a startling maze of passages branching off in all directions, some of them connecting back with the main passage. On my slowly evolving sketch, I began to see that there was a roughly triangular grid-like layout. These passages were far muddier than the main corridor, probably because it hadn't been washed down to cobbles by the small stream. After a dozen shots, we'd worked our way back and forth through the maze into a section of confusing breakdown blocks and seemingly cospatial yet non-intersecting passages. Hodags lurked around every corner. The farther we went, the muddier we got. Edgard checked out an upper-level lead and a sleet of nearly liquid mud continuously rained down. Bob and I could no longer keep the data clean and my muddy erasings had worn a hole through the tough Rite-in-the-Rain paper. Everyone was cold and slimed so we decided to call it a day after closing a loop. Normally I fill two or three sheets of paper with sketch but this maze wound around so much that I'd fit seventeen stations of our survey onto less than half a page! There is still one obvious lead in the maze which can be cleaned up easily next time.

After a dozen shots, we'd worked our way back and forth through the maze into a section of confusing breakdown blocks and seemingly cospatial yet non-intersecting passages. Hodags lurked around every corner. The farther we went, the muddier we got. Edgard checked out an upper-level lead and a sleet of nearly liquid mud continuously rained down. Bob and I could no longer keep the data clean and my muddy erasings had worn a hole through the tough Rite-in-the-Rain paper. Everyone was cold and slimed so we decided to call it a day after closing a loop. Normally I fill two or three sheets of paper with sketch but this maze wound around so much that I'd fit seventeen stations of our survey onto less than half a page! There is still one obvious lead in the maze which can be cleaned up easily next time.

The hour was still fairly early by previous Bratwurst survey standards and we hadn't seen many of the sights so we left the survey gear behind and headed upstream to poke around (and plan for the next survey). Beyond the surveyed passage from last time we found a nice maze of mostly dry passage controlled by thin joints in the ceiling. The ceiling was rarely more than four feet high, but the floor was sandy and the walls solid rock, not the earlier Crisco. I poked up the stream passage as far as I could easily get, but turned around when faced with a breakdown and mud choke. Tom followed and tried pushing some of the marginal leads but to little avail. Edgard tried a different lead and had somewhat more success. He came back looking leperous in a coating of mud on all surfaces. We chalked it up as something for another day, took some photos for the Swarthmore magazine (Tom, Edgard and I are alumni), and started the laborious trip back out of the cave.

The hour was still fairly early by previous Bratwurst survey standards and we hadn't seen many of the sights so we left the survey gear behind and headed upstream to poke around (and plan for the next survey). Beyond the surveyed passage from last time we found a nice maze of mostly dry passage controlled by thin joints in the ceiling. The ceiling was rarely more than four feet high, but the floor was sandy and the walls solid rock, not the earlier Crisco. I poked up the stream passage as far as I could easily get, but turned around when faced with a breakdown and mud choke. Tom followed and tried pushing some of the marginal leads but to little avail. Edgard tried a different lead and had somewhat more success. He came back looking leperous in a coating of mud on all surfaces. We chalked it up as something for another day, took some photos for the Swarthmore magazine (Tom, Edgard and I are alumni), and started the laborious trip back out of the cave. The retreat was without incident until the very end. Edgard lead the way back through the Miseries and up through breakdown to the bottom of the pit. By the time I'd finished the laborious belly crawling, he had come back to report...

The retreat was without incident until the very end. Edgard lead the way back through the Miseries and up through breakdown to the bottom of the pit. By the time I'd finished the laborious belly crawling, he had come back to report... "We have company, and they have a broken leg!" Suddenly things became more urgent.

"We have company, and they have a broken leg!" Suddenly things became more urgent.The Rescue

After the fall: Mike Masterman sitting pretty as the rescue starts to mobilize. (Tom Kornack photo) |

It was unclear exactly what happened; the story they told was that, they were trying to ascend out of the pit on their rope when Mike's ascender jammed about 15' up. He fell while trying to change over onto rappel on the other rope. Apparently Mary had also suffered an ascender jam but had worked her way through it. A lone Jumar could be seen (just the Jumar, nothing else) about 15 or 20' up the rope.

It was unclear exactly what happened; the story they told was that, they were trying to ascend out of the pit on their rope when Mike's ascender jammed about 15' up. He fell while trying to change over onto rappel on the other rope. Apparently Mary had also suffered an ascender jam but had worked her way through it. A lone Jumar could be seen (just the Jumar, nothing else) about 15 or 20' up the rope. Whatever the problem had been, we had to deal with the aftermath. Mike appeared warm, well-fed, hydrated and otherwise stabilized. We didn't need all five people at the bottom of the pit sitting on our hands until help arrived. I ascended to help coordinate the rescue efforts, touch base with Mary and fetch more warm clothing for everyone. It was a singularly tense time wondering if maybe there was something wrong with the rope, thus it was with great relief that I cleared the lip into the dark, rainy night. Edgard started up. I went to pillage the cars for any available rope, webbing, and any other rescue paraphernalia I could find. Fortunately, the rain was light and the temperatures were quite comfortable.

Whatever the problem had been, we had to deal with the aftermath. Mike appeared warm, well-fed, hydrated and otherwise stabilized. We didn't need all five people at the bottom of the pit sitting on our hands until help arrived. I ascended to help coordinate the rescue efforts, touch base with Mary and fetch more warm clothing for everyone. It was a singularly tense time wondering if maybe there was something wrong with the rope, thus it was with great relief that I cleared the lip into the dark, rainy night. Edgard started up. I went to pillage the cars for any available rope, webbing, and any other rescue paraphernalia I could find. Fortunately, the rain was light and the temperatures were quite comfortable. I met Mary part way down the path on her way back up with a backpack load of warm clothing. The Cass Volunteer Fire Department arrived along with several EMTs. An ambulance was on its way as well, though there would be nothing for them to do for some time yet. One of the fire department people and I carried a Stokes basket up the rough trail. This resembles a big sled with a metal railing all the way around it. The victim is laid in it, strapped in with four or five seat belt buckles and hauled out of the pit oriented either horizontally or vertically. Over the next half hour, four or five pickup trucks full of other folks arrived and it was becoming quite an Event.

I met Mary part way down the path on her way back up with a backpack load of warm clothing. The Cass Volunteer Fire Department arrived along with several EMTs. An ambulance was on its way as well, though there would be nothing for them to do for some time yet. One of the fire department people and I carried a Stokes basket up the rough trail. This resembles a big sled with a metal railing all the way around it. The victim is laid in it, strapped in with four or five seat belt buckles and hauled out of the pit oriented either horizontally or vertically. Over the next half hour, four or five pickup trucks full of other folks arrived and it was becoming quite an Event. The fire department rigged a couple of pulleys from trees and brought out the largest caliber rope I have ever seen. Bob emerged from the pit at this point as well leaving Tom and Todd to keep Mike company. Six or eight of us lowered Wayne Cassell, one of the EMTs, along with the Stokes basket down the pit to coordinate things down there. I volunteered my vertical services and rappelled part way down to lower a backboard and bag of supplies to Wayne and Tom below. More people were summoned for the much more difficult task of hauling people out of the pit.

The fire department rigged a couple of pulleys from trees and brought out the largest caliber rope I have ever seen. Bob emerged from the pit at this point as well leaving Tom and Todd to keep Mike company. Six or eight of us lowered Wayne Cassell, one of the EMTs, along with the Stokes basket down the pit to coordinate things down there. I volunteered my vertical services and rappelled part way down to lower a backboard and bag of supplies to Wayne and Tom below. More people were summoned for the much more difficult task of hauling people out of the pit. Mike was put in the Stokes in good condition and buckled securely. The idea was that everyone on the surface would directly haul the basket and Wayne out together. Even with a dozen people, this proved to be impossible. Edge rollers might have helped here, but there was no way we could haul a pair of 200-pound people out together without some sort of mechanical advantage. The alternative was hauling Mike out solo, but someone clearly had to accompany him to free the sled from numerous overhangs and jams. Tom was the most competent SRT (Single Rope Technique) person down there, I suggested that he ascend one of the other ropes in parallel with the basket and get it around the obstacles. Todd abandoned ship and climbed most of the way up one of the ropes. Tom got on the other rope (the one without the redirect to keep in out of the waterfall and chimney). Edgard and Mary wrapped the mainline around the a tree down the trail to bellay the ascent. The rest of us grabbed the rope and pulled. Hard. Slowly, ever so slowly, six inches at a time, the encapsulated victim came up.

Mike was put in the Stokes in good condition and buckled securely. The idea was that everyone on the surface would directly haul the basket and Wayne out together. Even with a dozen people, this proved to be impossible. Edge rollers might have helped here, but there was no way we could haul a pair of 200-pound people out together without some sort of mechanical advantage. The alternative was hauling Mike out solo, but someone clearly had to accompany him to free the sled from numerous overhangs and jams. Tom was the most competent SRT (Single Rope Technique) person down there, I suggested that he ascend one of the other ropes in parallel with the basket and get it around the obstacles. Todd abandoned ship and climbed most of the way up one of the ropes. Tom got on the other rope (the one without the redirect to keep in out of the waterfall and chimney). Edgard and Mary wrapped the mainline around the a tree down the trail to bellay the ascent. The rest of us grabbed the rope and pulled. Hard. Slowly, ever so slowly, six inches at a time, the encapsulated victim came up.  Though we were all sore and sweating from tug-o-war duty, the person doing the hardest work was definitely Tom. He was hanging by his harness for over an hour jammed under and behind the sled doing "crazy, desperate things" to keep Mike from getting more wedged in the narrow crack the rope had worked its way into. In retrospect, he says that he should have been slightly above the sled.

Though we were all sore and sweating from tug-o-war duty, the person doing the hardest work was definitely Tom. He was hanging by his harness for over an hour jammed under and behind the sled doing "crazy, desperate things" to keep Mike from getting more wedged in the narrow crack the rope had worked its way into. In retrospect, he says that he should have been slightly above the sled.  At long last, at 2am, roughly four hours after the fall occured, Mike emerged from the hole with an exhausted Tom close behind. It turns out that Mike is a former member of the Cass fire squad and got unmitigated flack from everyone. "Hell, Masterman! If we'd'a known it was you, we'd'a left ya down there!" Nevertheless, seven of us carried Mike down the rough trail to the waiting ambulance and paramedics where he was taken to Elkins.

At long last, at 2am, roughly four hours after the fall occured, Mike emerged from the hole with an exhausted Tom close behind. It turns out that Mike is a former member of the Cass fire squad and got unmitigated flack from everyone. "Hell, Masterman! If we'd'a known it was you, we'd'a left ya down there!" Nevertheless, seven of us carried Mike down the rough trail to the waiting ambulance and paramedics where he was taken to Elkins. The litter-bearers staggered back up the hill to extract Wayne from the depths. Fortunately, he could fend off the obstacles by himself and his retrieval went smoothly. With the excitement over, people started taking down rigging, redistributing comandeered gear to their rightful owners and transporting it back to the car. We pulled up the ropes and transported the piles of gear back to the car, most of it slimed and nasty by association.

The litter-bearers staggered back up the hill to extract Wayne from the depths. Fortunately, he could fend off the obstacles by himself and his retrieval went smoothly. With the excitement over, people started taking down rigging, redistributing comandeered gear to their rightful owners and transporting it back to the car. We pulled up the ropes and transported the piles of gear back to the car, most of it slimed and nasty by association.  My whole team and I were righteously tired and it was all we could do to drive back to basecamp. I've never had my knees buckle under me! Despite working up a powerful hunger, it was all we could do to choke down some pasta and sauce; at 3:30 in the morning, your digestive system is closed for the night. Showers and sleep followed in rapid succession.

My whole team and I were righteously tired and it was all we could do to drive back to basecamp. I've never had my knees buckle under me! Despite working up a powerful hunger, it was all we could do to choke down some pasta and sauce; at 3:30 in the morning, your digestive system is closed for the night. Showers and sleep followed in rapid succession.

Aftermath

If not fun, it was definitely interesting to see and participate in a rescue situation. It's definitely better to participate from this side! The next day we were all feeling pretty smug despite the pain-induced, sleep-deprived haze. The whole incident shows that potentially fatal accidents can happen even to competent, well-equipped cavers. Caution and extreme care must be taken around vertical work. The whole process makes me even more glad that I was able to evacuate under my own power after my own 15' fall. Then again, I didn't have 96' of pit to get around and all my body parts were in the right places. I look forward to hearing how Mike's recovery is going. It is also fortuitious that we turned the survey when we did. Had we arrived at the bottom a few hours later, we would have just added to the pandemonium rather than helped lessen it. All told, we surveyed perhaps 200' of difficult, slimy passage. Next time, I'm headed for the more rewarding, more linear trunk passage upstream in the Bratwurst. When the going gets Wurst...

It is also fortuitious that we turned the survey when we did. Had we arrived at the bottom a few hours later, we would have just added to the pandemonium rather than helped lessen it. All told, we surveyed perhaps 200' of difficult, slimy passage. Next time, I'm headed for the more rewarding, more linear trunk passage upstream in the Bratwurst. When the going gets Wurst...

Tom's Perspective

(by Tom Kornack)

It turned out that it was very fortunate that we turned in anomalously

early. We made great time going back to the pit, driven by delusions

that some luscious pizza awaited us in Dunmore. (The pizza place was

certainly closed; it was enough to simply imagine the possibility.) I

was bringing up the rear out of the miseries when I heard the news that

there was a party of three in the pit and that one of them had suffered

a broken leg. It was immediately clear that we would have to

participate in the rescue. When I finally reached the bottom of the

pit, I found a chipper and embarrassed Mike Masterson sitting up in the

middle of the room, just out of the waterfall. Both bones in his left

leg has obviously been broken because the angle of his foot did not

correlate with the angle of his kneecap. They had applied an effective

splint using two straight 4 cm dia. sticks on either side and copious,

tight wrapping of some red webbing. His friend Todd was nearby, trying

to stay warm, but actively feeling cold. Just as I reached them, I

heard Mary at the top of the pit, getting off rope and heading off to

find help. Charles immediately ascended to get us some clothing. Edgard

followed him up. Bob replaced the clear plastic sheet that was covering

Mike's legs with his space blanket. Bob ascended soon thereafter. I

spoke with Mike continuously while we were down there and I could not

detect any evidence of hypothermia: he could divide 90 by 11 and was

able to explain and defend the physics of his company's products very

clearly. At this point, it was myself, Todd and Mike at the bottom of

the pit. Mike's injury did not seem to bother him too much. While we

waited for the rescue folks to arrive, Todd became increasingly cold.

Wayne Cassell was lowered into the pit by the team of rescuers

assembled on the surface. He was directly attached by a carabiner at

the waist to the railing of a Stokes basket. He was simultaneously

rappelling off a second safety line. Unfortunately, he came down

through the waterfall, which eventually disabled his radio. The rope

was also placed in an unfortunately tight pinch in the rock, ultimately

making it difficult haul. It was determined immediately thereafter that

we were required to use a back board and other immobilization so we

waited while the back board was obtained and lowered into the pit.

Meanwhile, Wayne covered Mike in a wool blanket and checked the leg for

bleeding, sensitivity and other signs of trauma. Wayne's radio suddenly

went to static due to the water from the waterfall. We finally got the

back board and Mike was able to move himself onto the board and we

wrapped his tightly in the wool blanket. A neck brace was applied and

his head was immobilized using foam blocks. We put a `zipper' over his

body, which firmly strapped his body to the board in about six places.

Once he was firmly affixed to the back board, we could lift him into

the Stokes basket. We tightly laced some webbing across the basket

railings, thereby affixing Mike to the Stokes basket. We fashioned a

foot loop for his good foot, so that he could hold his body up and keep

weight off his broken foot when the basket was vertical. He was ready

to go up.

We connected the haul line to the railing at the top of the Stokes

basket, near to Mike's head. Wayne attached himself directly to the

Stokes basket as he had done before and the surface crew began to haul.

They could lift the Stokes basket relatively easily but as soon as they

had to lift Wayne, they could haul no further. The surface crew tried

several times to no avail. It was then decided that I should ascend in

parallel with the Stoke's basket and guide it along the way. I should

mention here that I have no experience with rescue work, so I did my

best and probably made several mistakes. I thought that I should follow

Wayne's example and guide the Stokes basket from the bottom. This

worked well while we were ascending through the first 1/2 of the pit,

where our lines were roughly vertical and the sled was not in contact

with the wall. We were ascending directly in the waterfall, which gave

both of us some discomfort. We first got stuck when we reached the

point where both the haul line and my line were channeled through a

tight pinch in the rock. At that point I found that I really needed to

be above the basket in order to guide it out and away from the pinch.

Unfortunately, we were still in the waterfall at this point. I managed

to ascend up behind the basket from the bottom and was able to push the

basket out from the pinch. We were in a very tight area and I needed

the haul team to provide just one tug at a time. Of course, the haul

team was eager to haul up, so they always tried to keep pulling. Twice

this resulted in the basket being wedged against an overhanging bit of

rock before I could guide it away. I think that we were eventually able

to communicate the need for small tugs, though I later understood that

the haul team was nonetheless frustrated by the lack of good

communication. After we escaped the first pinch, the basket turned

sideways and slid into a vertical crack, threatening to crush Mike's

face if it slid in any farther. It was clear that a face shield would

have been a very effective and welcome addition to the Stokes basket. I

was helpless to pull the basket out because my rope was stuck behind

the basket in the crack and I could not let go of the bottom of the

basket to ascend because the basket would have leaned further into the

crack. Todd was just above us on the ledge at this point, and I asked

him to descend down to pull the basked out and away from the vertical

crack from above. He undid the rebelay and came down and did this. This

was immensely helpful. Again, I could have been a lot more effective if

I had been above the sled. The last bit of the haul went flawlessly. At

this point our ropes began to diverge, but I was nonetheless able to

pull the sled over and away from the last of the overhanging rock. I

was discharged of my duty and ascended up to the anchor tree. I

followed the group carrying Mike back to the Ambulance.

Others on this list have provided some decent explanations as to how

the fall originally happened. I will not speculate further. I did

ascend on the rope from which Mike fell and found absolutely no

problems, puffs or other concerning spots. I was particularly impressed

with the professional behavior and patience of all members of the

rescue effort; I directly benefitted from their responsiveness to my

needs and commands while ascending. I would appreciate any constructive

comments to learn how we might be able to have done things better with

the resources we had.For the first time since I had begun surveying with the Gangsta

Mappers, our survey team decided to quit early. We were awfully cold

and tired after worming around in the newly annointed `Hodag's Lair'

mazework: Charles Danforth zipped around, above and below us trying to

get a handle on how to sketch the maze. Bob Robins stoically managed

the survey data and drew cross sections. Edgard Bertaut (foresight)

pushed some particularly tight and muddy cracks and managed to slime us

all merely by proximity. I took backsight was particularly pleased with

the performance of my prototype electroluminescent panels on the survey

instruments. They really improved the comfort of the surveyor by

obviating the need to hold a light far and above the dial window. I was

nonetheless fatigued by surveying the nontrivial, nonorthogonal, and

nonplanar passages in the Hodag's Lair. As it was still early, we

decided to generate some body heat by exploring back towards the end of

the Bratwurst. The passage continues quite a ways back and pinches out

when it rises sharply over and into piles of breakdown. The passage

splits several times and makes some curious turns at odd angles. It

will be very interesting to see what the survey back there looks like

on the final map; I think this is one place where the survey will

really elucidate what is happening in the rock.

Further Aftermath (Sept 24, 2002)

According to Todd Leonhardt:

The details on the incident with Mike are basically as follows:

At approximately 8pm on Saturday evening, Mike Masterman, Mary Schmidt, and

myself descended into the Pit entrance of Cassell Cave in Pocahontas County

with the plan of doing a Pit-to-Windy through trip. As we were suiting up

at the cars, it began to rain. The rain continued to increase in intensity.

I was the last person in the cave. I was completely soaked to the bone

before I started rapelling, by the time I was at the bottom I was cold and

shivering. Given that I was alreay completely soaked, hadn't slept in about

36 hours, and it was going to be about a 6 hour fairly rigorous trough trip,

I thought it would be best to bag the trip, ascend up and call it a night -

I didn't want to risk getting hypothermic. The others on the trip agreed.

Mike decided to ascend up first, in case I needed any help getting over the

lip at the top. Mike got up the rope a little over 10 feet and said he was

tired - he had helped someone put the roof on a barn that morning, plus I

think his ascending system wasn't tweaked quite right and it was taking him

longer to ascend than it should. So we told him he needed to change over to

rappel and come down and we'd figure things out from there. He started to

switch over to rappel, but one of his ascenders was jammed and he couldn't

get it undone (the torrential downpour had coated the ropes with mud). This

was a very bad situation because the bottom 30+ feet involves ascending

through a small waterfall, which was made significantly worse by the hard

rain. There was a 2nd rope from the gangsta mappers who were surveying in

the cave, so I ascended up that to help Mike. On the way up, some of Mike's

gear feel and hit my helmet, causing my light to stop working - fortunatey

it was a duo and I just switched bulbs. It turns out that one of the things

that fell was his footloops - don't ask me how they managed to come off his

ascender - I don't have a clue, maybe he purposely took them off, maybe not

- at this point it was obvious that he was getting severely hypothermic and

not thinking straight. I knew that without his footloops to stand up in,

the situation had just gone from very bad to truly frightening. We tried to

get Mary to throw them up or tie them to the rope or something so we could

haul them up, but the communication just wasn't working (it was hard to hear

because of the waterfall). So I told him to put his feet on me and stand up

and get the ascender off. At this point, he was really not thinking

straight, first he just tried undoing the cam on his ascender, so I told him

he had to move his ascender up first - he did just that - moved it up and

tried to undo the cam, I explained again that he needed to undo it while

moving it up a little bit. At some point Mike said he was losing it and

couldn't hang on much longer and asked for a kife to cut himself loose. If

we had one, we would probably have cut him loose, but none of us had a

knife. After a few more tries, we were able to get Mike's ascender

un-jammed. Problem is, he was rappeling with a figure-8 and hadn't locked

it off (and I hadn't bothered to check). So as soon as his ascender came

off, he dropped like a rock.

Regarding Mike's condition:

Apparently it is a rather nasty break that Mike has. He had surgery around

8am Sunday morning and some pins got put in. He will probably need another

surgery at some point.

The Wilderness Journal

Neithernor

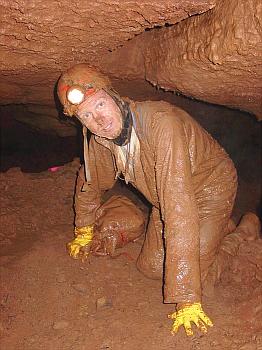

He ain't clean no more! Edgard after battling a few more hodags in the farthest reaches of the Bratwurst.

He ain't clean no more! Edgard after battling a few more hodags in the farthest reaches of the Bratwurst.